How Game Theory Benefits Attorneys and Litigators

January 15, 2021In this episode…

What if you, as an attorney, litigator or related legal professional, had a tool to predict how your cases would transpire? How would you use that tool to benefit your cases, clients, and business?

Bruce Bueno de Mesquita is a political scientist and renowned expert on game theory—the study of how mathematical models can strategically predict the decision-making process. Over the past 40 years, Bruce has developed a predictive and dynamic game theory model that has been used by attorneys, foreign politicians, the U.S. government, and more. So, what is the secret to Bruce’s extremely accurate model, and how could it help you in your profession today?

In this episode of the Engaging Experts Podcast, Rise25 Co-Founder John Corcoran sits down with Bruce Bueno de Mesquita, the Silver Professor of Politics at New York University, and Russ Rosenzweig, the CEO and Co-Founder of Round Table Group, to talk about game theory. Listen in as Bruce explains the ins and outs of his game theory computer model, how his model can benefit many different professions, and what his predictions are for America’s future political climate. Stay tuned!

Episode Transcript:

Note: Transcript has been lightly edited for clarity.

Guests:

John Corcoran, Co-Founder, Rise25

Russ Rosenzweig, CEO and Co-Founder, Round Table Group

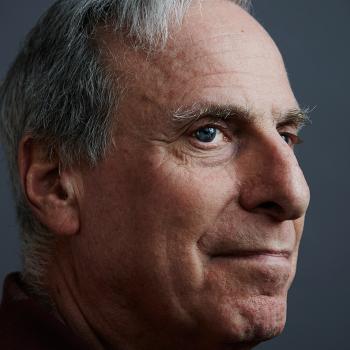

Bruce Bueno de Mesquita, Emeritus Senior Fellow at the Hoover Institution and the Silver Professor of Politics at the New York University (NYU)

Introduction: Welcome to Engaging Experts, the podcast that goes behind the scenes with influential attorneys. Our guests will describe their practice and expertise. Then we will go deep on various topics related to effectively using expert witnesses.

John Corcoran: Hey everyone, John Corcoran here. I am one of the co-hosts of this show, and we have got a great guest for you. He is a celebrated, amazing individual, who has acquired a wealth of knowledge and experience, which we will get to in just a second. But before I do, this episode is brought to you by Round Table Group, the Experts on Experts®. For more than 25 years Round Table Group has helped litigators to locate, evaluate and employ the best and most qualified expert witnesses. Round Table Group is a great complement to any litigator’s quest for expert witnesses and their search is always free of charge. A skilled team will review the complaint or patent and discuss all the nuances and details of the perfect expert. The team will perform thorough, comprehensive research and contact the candidates to check for conflicts and confirm their availability. This saves attorneys hours of time in the search for their next witness. Visit roundtablegroup.com or contact them at engagingexperts@roundtablegroup.com.

Today’s guest has an impressive background, Professor Bruce Bueno de Mesquita is an Emeritus Senior Fellow with the Hoover Institution, and the Silver Professor of Politics at New York University. He is an expert on foreign policy in nation building. His current research focuses on political institutions, economic growth and political change. He is also known for his research on policy forecasting for national security and for business concerns. His most recent book is The Spoils of War: Greed, Power, and the Conflicts That Made Our Greatest Presidents, with Alastair Smith. Bruce is the author of 24 different books, about 150 different articles, and has been profiled in all kinds of different media as well. He received his BA degree in 1967 from Queens College, received his MA degree in political science, and his PhD from the University of Michigan. Bruce, it is an honor to have you here. I have with me also the CEO and Co-Founder of Round Table Group, Russ Rosenzweig.

Russ, I want to hand it over to you because you possess an interesting background with game theory, which, of course, is Bruce’s specialty. I will turn it over to you to just tell us a little about that background and history.

Russ Rosenzweig: Sure, John, I am thrilled to introduce Bruce because he has a small but important role to play in the founding of Round Table Group. Over 25 years ago, I was studying game theory at Northwestern University and I had the privilege of studying with some superstars like Roger Myerson who went on to win the Nobel Prize in Economics. Secretly, I also love taking history classes, comparative religion classes and political science classes. Bruce has weaved together all these fields into a beautiful dynamic tapestry of different kinds of areas of expertise. It was because of people like Bruce, Roger, and the many other world class teachers that I studied under in college. That was the whole inspiration for founding Round Table Group. To bring people like Bruce to the world of commerce and to help them. Rock stars typically have agents and business managers. We wanted to help experts like Bruce to be engaged more frequently in consulting commercial context, and in the expert witness context, which is what Round Table Group’s focus is. The reason I am so thrilled to have Bruce here as one of our first pioneering podcast participants, is because unlike the thousands of other experts that we spend our time introducing to lawyers to serve as expert witnesses, Bruce has a product, a technique, and a framework for helping lawyers regarding settlement agreements. John, you know 99% of cases settle, though it could take months or years before people finally get around to getting serious about settlement discussions. Among Bruce’s many topics of expertise, the one I really want to highlight here is his ability to help lawyers using game theory. How to figure out what a likely settlement agreement will be like and have an ability to change that amount and make it higher or lower based on several techniques, arguments, persuasion and skills. Bruce has mastered this art and not a lot of lawyers know about Bruce and Round Table Group’s ability to help them with regard to settlement agreements. I’m so thrilled to introduce Bruce and have you guys really discuss this in more depth.

John Corcoran: Thank you, Russ, for that great introduction, and, Bruce, I want to turn to you. For those who stumble upon this episode, and at the risk of dumbing it down a little bit, could you explain applied game theory to all the listeners?

Bruce Bueno de Mesquita: Sure. Thank you, Russ, for your kind remarks. Applied game theory is a way of understanding how people deal with each other strategically, taking into account what they believe the other person is going to do if they make this choice, that choice, or a different action. It is playing multidimensional chess. In the context of litigation, there are always multiple players and multiple stakeholders with an interest in shaping what the outcome of settlement discussions will look like. Game theory is a tool. If you use the dynamic model, it can help you understand what other people will do. What makes them do what you would like them to do? How can you get them to make a deal that is better for you?

John Corcoran: Great summation. You have a computer model that you have been developing for 30 years or so that applies all this, correct?

Bruce Bueno de Mesquita: The process is computerized, and it takes surprisingly little information to work out what other people are going to do and what you can do to change what they are going to do. All you need to know is: who is trying to influence the decision of every one of those people? What did they say they want? What is the outcome they are advocating, not what is in their heart of hearts? What do they say they want and what is the strategy? How high a priority is it for them? They face many other issues. How important is this particular problem? How open are they to listening to counter arguments to your argument? How much clout can they bring to bear? Can they veto the outcome or not? If you know those few things you can work out with more than 90% accuracy what everybody is going to do, what everybody will agree to, and how you can get them to agree to an outcome that is closer to what you want than what they want. In the litigation settlement arena, this model has been used a number of times and on average it produces 25 to 40% better settlement terms than the client expected. Whether they are as they usually are on the defense side, or as they occasionally are on the plaintiff side, lower cost when they are the defendants and higher costs when they are the plaintiffs. People have a lot of money on the table.

John Corcoran: One thing that I find fascinating about this is that you have given it in a range of places, including foreign nationals. There was a study by the CIA that found your predictions for the computer model hit the bullseye twice as often as their own analysts’ predictions. How is it that you developed a model that works well both in that context and in the context of litigation?

Bruce Bueno de Mesquita: Early on, I realized that litigation and international conflict are exactly the same problem, and pretty much all business discussions, that are not driven by market forces, are the same problem. That is, there are people on different sides that are trying to persuade the other side to do what they want through a mix of making settlement offers and coercive pressure; making it costly not to do what they want, and you have the choice. You can make a deal, or you can fight back. You can walk away and so forth. That is what war is. That is what litigation is. That is what mergers and acquisitions are. That is pretty much what all issues in life that are not driven by markets are. When I had that insight, I wrote a computer model. The original model was very primitive, and it turned out to capture the attention of the U.S. intelligence community because it made some predictions that were different from what they were expecting on the issues at the time, and it turned out to be right. The intelligence community has used that model approximately 2,000 times, and it is, as I said, the same problem for lawyers as it is for the intelligence community.

John Corcoran: You have probably observed a tremendous number of attorneys and litigators use this model. What are the most successful applications that you have seen? How do you see lawyers use it to their advantage? Do you see this as a more flexible negotiator? Give me some metrics of success that you see from the lawyers who are using this model successfully.

Bruce Bueno de Mesquita: There is not an off–the–shelf right strategy for all problems. Each problem has a unique configuration of those variables that I mentioned for all the players, and that produces a unique optimal settlement. What are the characteristics of a lawyer who uses this successfully? A strong ego. A person who is willing to entertain the possibility that their data with a mathematical model can produce better solution concepts than they came up with on their own. That is a hard thing for a lot of people to accept. There are some attorneys I have worked with for decades; they have that characteristic. They have a deep interest in getting the best result for their client. They do not have a huge ego involvement with, “Do what I say,” as opposed to let’s look at other ways to look at the problem. That really is the key thing.

John Corcoran: I understand the model can provide round–by round–simulation of a negotiation. Then as things evolve and change during negotiation, you plug in these new metrics and things change. Explain that to me.

Bruce Bueno de Mesquita: OK. First the model itself is dynamic, so these round-by-round exchanges of information that occur within the model’s logic predicts what is optimal for me to say today? What will the response be, and what will it be tomorrow, and the next day, and the next day? It is not just constantly updating the information, the model has already projected step by step how the process will unfold and gives you insights into when we should stop talking and take this deal, because it is going to head in a bad direction, perhaps in the future, or it is getting better, and we should keep talking. There are times when new things are learned, where there is a realization that you need to make some change to the inputs because there’s been an external shock, which has changed the trajectory. I have, literally, on some litigations, sat in a room next door to where discussions are taking place, instructed the client to take a certain number of coffee breaks, come in and update me, and plug in some new data if necessary. Then, go back in into the room. Most of the time the model is correctly working out what the trajectory of the conversations are. The early models were all very primitive. Now the dynamics are quite powerful and so the user has really the opportunity to play out the negotiation before ever sitting down with the other side.

John Corcoran: It has to be that once you’ve used that model, you couldn’t imagine going back to not using that model when you’ve had that kind of road map to map it out for you. I’m curious, though, when you’re working with attorneys, how often does the model spit out a scenario or a suggestion that when you make it to the lawyer, and you say, “Here’s what you should do,” and then the lawyer says, “No way, no, I couldn’t do that,” or “I couldn’t imagine that it would produce the result that we’re looking for.” In other words, how often does it completely surprise them?

Bruce Bueno de Mesquita: Oh, quite often. I would say that 80% of the time the model produces an approach to the problem that differs from what the attorney had in mind. The percentage that would then say, “Oh no, there’s no way. That couldn’t possibly be right. It’s much smaller.” To tell an attorney, “You’re right, it’s going to play out just the way you think, pay me,” well they are like, “What have I got out of this,” right? The added value is to see a better way through the problem, where better defined is producing a result closer to what the lawyer wants for his or her client.

John Corcoran: I imagine there are a lot of attorneys that pick-up beers afterwards, saying, “You were right. You were right, I didn’t think it would work, but it worked.”

Bruce Bueno de Mesquita: I have tons of emails from attorneys that say, “It’s like magic. How did that happen? They did just what you said.”

John Corcoran: I imagine you only would represent one side, but are there ever any scenarios where if both sides are using the model, what happens?

Bruce Bueno de Mesquita: My dream is that both parties use the model, and I’ve spoken to mediation groups and so on, hoping that happens. What happens if it were used by both sides is that you would get to a settlement faster, at a lower cost to clients, and you would get to a settlement that was not optimal for one side, but jointly optimal. That, of course, is why it has never happened because once the client realizes that there is an optimal path to the best possible outcome they can get, it is not the same as that jointly optimal outcome. They want to go down the path for the best that they can get for their clients. I’ve had one occasion, it was not in litigation it was in a case where a firm had an internal battle and was splitting, where I persuaded the CEO of the firm to let me talk to the other side about doing a joint analysis. When I went to the leader of the opposite faction, he had experience with the model. He knew it worked. He had been under retainer with this firm for a long time. He said, “I know this works, but so and so sent you to talk to me, how can I trust that you are not really going to be doing what is good for them?” So, he did not do it. He would have been much better off if he had, but that is another matter.

John Corcoran: What about courts? Courts are always trying to do things more efficiently, and these days they have limited resources. Our courts seem to have a vested interest in widespread adoption.

Bruce Bueno de Mesquita I don’t think that is right. Courts do not have an interest in the outcome. The courts certainly have an interest in settlement because their dockets are packed. I could imagine judges routinely will say to attorneys in a dispute, “Go work this out,” but I would be surprised if they steered them towards using a tool. Arbitrators and mediators, I can well imagine that. Their interest is to see a settlement and they don’t have the same constraints on them that a judge has, but overwhelmingly in the litigation arena the people who use the model are attorneys, not the courts.

John Corcoran: This has been fascinating. Anything in particular that we haven’t covered that if I’m an attorney listening to this, and we haven’t used a model before, that we should know to persuade us that we should?

Bruce Bueno de Mesquita It is little work for the attorney. There is some upfront effort to assemble a small group of people who are knowledgeable about the problem. Those people will provide the input data. That is: Who are the stakeholders? What are they each likely to be advocating? How high a priority is it? They will never be asked what will happen. We know well from research by people like Phil Tetlock that experts know the facts, but they don’t have good judgment about how things will unfold in the future. That’s the model’s comparative advantage. Once the attorney puts that little bit of time in assembling a group of experts and gets those experts to sit down and answer the questions that will lead to numerical data about the variables.

The next commitment of the attorney is to listen to a briefing on how things are likely to unfold. Here are the things you can do to make them unfold better. Here is what you could get. Here is what you otherwise will get. Here is what you do to get it, and then they are off and running. My little consulting firm is always pleased to follow up after the briefing if there are any questions. Well, “Did you look at our doing this? Did you look at our doing that?” Generally, the answer is yes, but if the answer is no, we will go back. If they learn some piece of information that they believe is material and changes the input data, [for instance if] somebody has a heart attack and is no longer in the game or what have you, we will rerun it for them, and tell them if it mattered. If it mattered, how much did it matter? If their team of experts are uncertain about some of the data, for example, I don’t know how high a priority this is for so and so. Well, we will simulate it if it is this high or is that high, and if it generally doesn’t matter if there are several players, but if it does matter, then we will help the attorney to see innocuous things they can do to find out which is the right number.

Bruce Bueno de Mesquita: A little phone call, for example, to say to somebody, “I’d like to talk about this matter with you. Can we have lunch tomorrow?” If the answer is yes, this is a high priority for that person. If the person says, “I’m busy, call me in three months.” You know it is a low priority. You’ve pinned down that value and they do not know that they have given you data.

John Corcoran: That’s great. Now, over 40 years, computing power has changed tremendously, of course, and there’s a lot of talk, especially in the mainstream media about AI, the advent of AI. How do you see those changes in computing power and AI affecting your model?

Bruce Bueno de Mesquita: When I started doing this, I had an upper bound of about 12 players. Then it went to 47. They were just memory limits. Today, I can handle any finite number of players in a contest. When I started doing this in the project in the early 80s, for example, I was asked to make some predictions about changes in the Constitution of Turkey. I ran this on a commercial time on a mainframe computer and at the end of a week I had nothing because it had timed out. It couldn’t do all the calculations. Today by the time my finger comes off the button that tells the model to run, I have that solved and a projection two years into the future,

John Corcoran: Wow!

Bruce Bueno de Mesquita: Things have changed a lot. There are artificial intelligence components that I’ve designed in this model, but I had some such components 40 years ago. It was for its time a pretty sophisticated model. Today, the computational capabilities are such that it is just incredible how complex a problem can be, and you can solve it in a matter of moments.

John Corcoran: Fascinating. Before we wrap up, I wanted to get to the books you have in the works. Numbers 25 and 26, which are still on the way. Before I do that, you co-authored a book with an active sitting Secretary of State, Condoleezza Rice. That’s fascinating. It is not every day you hear about that sort of thing. What was that experience like?

Bruce Bueno de Mesquita: It was kind of a cool experience. Condi and I were colleagues at Stanford, and she and some other colleagues had a puzzle they did not know how to solve, how could people who were perceived to be way outside the mainstream of their country’s politics rise to the highest office? Two examples in the book are Ronald Reagan becoming president of the United States, and Yeltsin becoming president and founder of an independent Russia. I offered a simple model to explain that to Condi. Then, Bush got elected and she went off to Washington. We worked on the book while she was Secretary of State. I believe this is the only instance of an academic book, not a memoir, not a political book, but an academic book published by an academic press, The University of Michigan Press, done by any sitting cabinet minister. Certainly, the only one by a Secretary of State, and it was a lot of fun, and an interesting distraction for all of us.

John Corcoran: What a cool experience! You have two books coming up. One is Popes and Kings: Competition and The Creation of Western Exceptionalism, and the other is Domestic Political Instability, which you’re working on with Alastair Smith. Tell us more about them.

Bruce Bueno de Mesquita: No math or statistics are included in Popes and Kings. However, game theory, reasoning, and data evidence prove that variations across Europe in its prosperity, secularism, level of parliamentary government and democracy, tolerance for competing religions, and the origin of the Protestant Reformation, all show logically, and with evidence, to be products of an obscure agreement, the Concordat of Worms, signed between the Holy Roman Emperor and Pope Calixtus II, on September 23rd, 1122, 400 years before Martin Luther. You can from the logic of the Concordat, predict not only that something like the Protestant Reformation would happen, but when it would happen, and you can predict which parts of Europe would become wealthy, which would not become wealthy. Taking the conditions of the agreement in 1122 and looking at the differences in Europe today, you can predict differences in per capita income from the deal back then and you can predict differences in life expectancy. You can even predict differences per million population in the probability of winning Nobel prizes in the Sciences. The Concordat of Worms shaped modern Europe in a way that has been completely missed by historians and by political economists. So that’s what that book is about.

John Corcoran: Fascinating. And then Domestic Political Instability?

Bruce Bueno de Mesquita: Domestic Political Instability is about what leaders do in anticipation of their inner circle or the masses rising up against them. Not just in terms of crushing uprisings, but what it takes for them to make their government more democratic and more liberal, and what it takes to make their government more autocratic and more oppressive. This is grounded in theorizing that Alastair Smith and I have worked on for many years as well, with James Marrow and Randolph Siverson on what has come to be known as the selectorate theory, in a new format that is more dynamic and provides an explanation of the strategic decision to change how you govern.

John Corcoran: I think some people would kick me if I didn’t ask this last question, but we are recording this in December of 2020, and without getting into politics or anything like that, considering we’ve had a pandemic for the last nine months, is there anything I need to know about? In other words, anything you have modeled out that is on the way that I should probably be warned about? I just have to ask you that.

Bruce Bueno de Mesquita: Well, I will tell you something that the selectorate theory tells us, which is a good thing and will be a disappointing thing as well, whatever one’s politics are. The Biden Administration’s policies will not look different from the Trump Administration’s policies. The rhetoric will be different, but the policies will not be extremely different. Governments that depend on a large number of people to keep them in power have little wiggle room on policy. The United States is such a country. If you are China, where you depend on very few people, you can get huge swings in policy. You can get huge swings in the economy and so forth. That is not true in what I call large coalition governments and mature democracies. Also, I’m fond of pointing out to my students, for instance, that the United States is the largest economy in the world, and China today is the second largest economy. And then I asked them, and I will ask you, what was the second largest economy in the world in 1890?

John Corcoran: 1890? The second largest in 1890. I’m going to guess like the Ottoman Empire or something like that. No?

Bruce Bueno de Mesquita: No. China. In 18 months, China went through huge swings in policy. It went from being second largest to being a relatively minuscule economy in–between, and now it’s back to being second largest. Whereas large coalition governments like the United States chug along slowly, but steadily move up. There will not be big changes.

John Corcoran: Interesting. That is reassuring for people, who are a little concerned that China will take control of the U.S.

Bruce Bueno de Mesquita: Yes, yes it should be.

John Corcoran: Good to know. Bruce, this has been wonderful. Where can people start to find out more about you or find out more about the work that you do, or check out your books?

Bruce Bueno de Mesquita: Well, they can go to Amazon to find the books. They will love The Dictator‘s Handbook, which is the selectorate theory, without math. They can go to look me up at NYU. Look me up at the Hoover Institution. I’ve got a rather large web presence. A lot of people have things to say about me, bad, good, and indifferent. The selectorate theory has a Wikipedia page. The Dictators Handbook has a Wikipedia page. The Predictioneer’s Game, which is on this forecasting model, has a Wikipedia page. I have no involvement in any of those pages. I have a Wikipedia page. I don’t write Wikipedia pages. I just do my thing. hey can Google me.

John Corcoran: Google the name. You can find all those links.

Bruce Bueno de Mesquita: Excellent. There are not a lot of Bueno de Mesquitas out there. Though, more than you would think.

John Corcoran: Thanks so much, Sir.

Bruce Bueno de Mesquita: Thank you.

Subscribe to Engaging Experts Podcast

Share This Episode

Go behind the scenes with influential attorneys as we go deep on various topics related to effectively using expert witnesses.

Bruce Bueno de Mesquita, Silver Professor of Politics at New York University

Bruce Bueno de Mesquita is the Silver Professor of Politics at New York University and an Emeritus Senior Fellow at the Hoover Institution. Bruce is an expert on foreign policy and nation building, and his current research focuses on political institutions, economic growth, and political change. In addition to this, Bruce has written over 100 academic articles and 24 books and has been recognized by Foreign Policy as one of the top 100 global thinkers.

Many cases require the retention of an economics expert, and the specifics can span a range of focus areas including valuation, profits or losses, damages, and more. Our economics expert witnesses, speakers, and consultants are scholars from major universities and industry professionals.

Game theorists study mathematical models of the interaction between rational decision-makers. Game theory can be applied within multiple fields including system science, computer science, and logic. It can also be used as a term that describes logical decision making in computers, humans, and animals.

Negotiation is the bargaining process between two or more parties. Each side has their own requirement, goals, and perspectives. They seek to find common ground, reach an agreement, settle a problem that affects both sides, or settle a conflict. Through the negotiating process, the parties try to avoid arguing and reach a compromise.