Trends in Expert Witnessing: Narrowing Paths to Admissibility

By Noah Bolmer

The landscape for expert witnesses is shifting in ways that narrow the pool of admissible experts in various states. These changes are already producing exclusions in medical malpractice litigation and signaling a broader trend that could extend into engineering, forensic sciences, and financial testimony. For professionals who serve as experts, the challenge is not only to demonstrate credibility, but also to remain within the boundaries of these evolving standards.

The Shrinking Pool of Expert Witnesses

Legislatures and courts are increasingly demanding that testimony come from professionals who are not only qualified but also actively engaged in their specialty. This has created a situation where experienced experts may be excluded—not because their knowledge is unreliable, but because they do not meet statutory definitions of eligibility. The impact is particularly visible in medical malpractice, where new statutes require specialty or subspecialty congruence, but similar narrowing is occurring in other fields, with engineering experts needing active licensure and forensic scientists facing accreditation requirements. The result is a smaller, more selective pool of experts who meet these heightened standards.

Credential Gatekeeping

Typically, states have adopted either explicitly, or slight variations on the Daubert or Frye standards for expert admissibility. Over the past decade or so, state courts have enacted a series of statutes that inform that analysis.

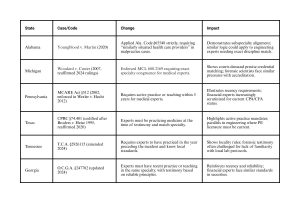

In Youngblood v. Martin, the Alabama Supreme Court applied Ala. Code §65548 to exclude a physician who was not a “similarly situated health care provider,” in demonstrating how subspecialty alignment can determine eligibility. Michigan’s Supreme Court has enforced MCL 600.2169 to require exact specialty congruence, as seen in Woodard v. Custer, where experts outside the defendant’s board certification were barred. Pennsylvania’s MCARE Act §512 requires active practice or teaching within five years, and courts have excluded experts who failed to meet this recency threshold, such as in Wexler v. Hecht. Texas reinforced specialty matching under CPRC §74.401, building on the precedent of Broders v. Heise, where an emergency physician was excluded from testifying against a neurosurgeon. Tennessee’s statute, T.C.A. §2926115, adds a locality requirement, demanding familiarity with community standards and thereby limiting portability for out of state experts.

Although medicine is at the epicenter of these reforms, the principles are spreading. Engineering experts are increasingly required to hold active licenses and demonstrate recent field experience in construction defect cases. Forensic scientists face accreditation requirements in disciplines such as DNA analysis and ballistics, with courts skeptical of testimony from those lacking recognized certifications. Financial experts encounter growing scrutiny of professional credentials, with courts questioning testimony from economists or accountants who lack current CPA or CFA status. This credential gatekeeping is actively reshaping who qualifies to testify.

Experts who once relied on broad reputations or generalist knowledge are finding themselves excluded if they cannot demonstrate precise alignment with statutory requirements—eligibility now depends on meeting specific, codified standards. While statutes vary in significant ways, there are some key trends in recent legislature:

- Specialty or subspecialty congruence

- Active practice or teaching within a defined window, usually 1-5 years

- Active U.S. licensure

- Familiarity with locality

The common thread is a demand for active, recent, and credentialed engagement in the relevant specialty. Experts in dynamic areas should anticipate similar pressures and prepare accordingly.

Academia

Professors and researchers occupy a unique position in this tightening environment. Some statutes, like Georgia’s, allow recent teaching to count as active engagement, which preserves eligibility for academics who are actively instructing in clinical or technical fields. However, pure research roles or administrative appointments may not satisfy these requirements, particularly when subspecialty alignment is demanded. Courts may look for direct involvement in practitioners rather than theoretical expertise alone.

For academics, maintaining current syllabi, supervising applied work, and demonstrating subspecialty relevance may improve admissibility. The narrowing pool means that those who can show active teaching in the right specialty are increasingly valuable, while those outside these boundaries risk exclusion. The challenge is not whether academics are knowledgeable, but whether their engagement meets the statutory definitions of active practice or teaching.

Remaining Eligible in a Tightening Market

Maintaining active practice or teaching roles is essential to satisfy recency requirements. Licenses and certifications must be kept current, with multistate licensure offering broader opportunities in jurisdictions with strict rules. Subspecialty documentation is increasingly important, as courts demand precise alignment between the expert’s field and the defendant’s specialty. Continuous engagement in professional education and training can also help demonstrate ongoing relevance. Forensic Security Expert Tom Demont notes:

When you’re interviewing a forensic investigator, the first thing you want to ask him is how many credentials do you carry? I personally carry thirteen and I have to get recertified every three years on all those credentials. [. . .] Somebody is checking up on me and I’m just not hanging a shingle out there and saying, ‘I’m a certified master locksmith. I took the exam in 1985, and nobody has checked it since then.’ It doesn’t work like that.

Experts cannot assume that past credentials will suffice; they must anticipate statutory demands and prepare evidence of compliance. This includes keeping certifications up to date, documenting subspecialty work, and ensuring that professional activity remainscurrent. Those who take these steps will not only remain admissible but also position themselves as scarce resources in a tightening market.

Opportunity in Scarcity

This narrowing has created a market dynamic where eligible experts are in higher demand. Specialists who meet the tightened criteria may command premium fees. At the same time, the exclusion of semi-retired or broadly trained experts reduces competition to some degree, concentrating opportunities among those who remain compliant with statutory requirements.

Law firms must compete for a smaller pool of admissible experts, and those experts can leverage their eligibility into stronger negotiating positions. For professionals who remain within the admissible pool, the tightening of rules is not only a challenge but also a source of competitive advantage. Eligibility itself has become a marker of value in the expert witness marketplace.

Conclusion

For experts, the path forward is clear: remain actively engaged, maintain credentials, and document subspecialty relevance. The pool of admissible experts may be shrinking, but those who adapt to these standards will find themselves in a position of heightened demand and influence.

For over 30 years, Round Table Group has been connecting litigators with skilled and qualified expert witnesses. If you are interested in being considered for expert witness opportunities, contact us at 202-908-4500 for more information or sign up now!